While I love Django dearly, and I think the rate of progress we keep on the project draws a fine balance between progress and backwards-compatibility, sometimes I look ahead to the evolving Web and wonder what we can do to adapt to some more major changes.

We're already well-placed to be the business-logic and data backend to more JavaScript-heavy web apps or native apps; things like Django REST Framework play especially well into that role, and for more traditional sites I still think Django's view and URL abstractions do a decent job - though the URL routing could perhaps do with a refresh sometime soon.

The gaping hole though, to me, was always WebSocket support. It used to be long-poll/COMET support, but we seem to have mostly got past that period now - but even so, the problem remains the same. As a framework, Django is tied to a strict request-response cycle - a request comes in, a worker is tied up handling it until a response is sent, and you only have a small number of workers.

Trying to service long-polling would eat through your workers (and your RAM if you tried to spin up more), and WebSockets are outside the scope of even WSGI itself.

That's why I've come up with a proposal to modify the way Django handles requests and views. You can see the full proposal in this gist, and there's a discussion thread on django-developers, but I wanted to make a blog post explaining more of my reasoning.

The Abstraction

I'm going to skip over why we would need support for these features - I think that's relatively obvious - and jump straight to the how.

In particular, the key thing here is that this is NOT making Django asynchronous in the way where we make core parts nonblocking, or make everything yield or take callbacks.

Instead, the key change is quite small - changing the core "chunk" of what Django runs from views to consumers.

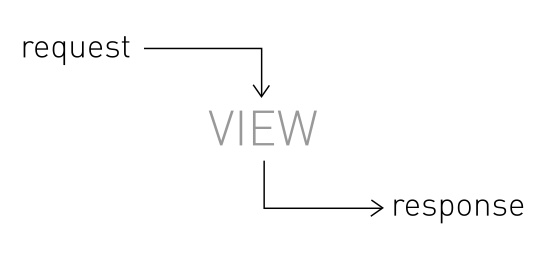

Currently, a view takes a single request and returns a single response:

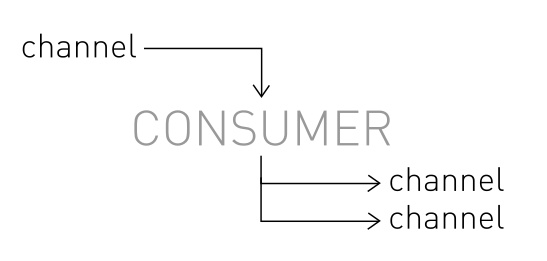

In my proposed new model, a consumer takes a single message on a channel and returns zero to many responses on other channels:

The code inside the consumer runs like normal Django view code, complete with things like transaction auto-management if desired - it doesn't have to do anything special or use any new async-style APIs.

On top of that, the old middleware-url-view model can itself run as a consumer, if we have a channel for incoming requests and a channel (per client) for outgoing responses.

In fact, we can extend that model to more than just requests and responses; we can also define a similar API for WebSockets, but with more channels - one for new connections, one for incoming data packets, and one per client for outgoing data.

What this means is that rather than just reacting to requests and returning responses, Django can now react to a whole series of events. You could react to incoming WebSocket messages and write them to other WebSockets, like a chat server. You could dispatch task descriptions from inside a view and then handle them later in a different consumer, once the response is sent back.

The Implementation

Now, how do we run this? Clearly it can't run in the existing Django WSGI infrastructure - that's tied to the request lifecycle very explicitly.

Instead, we split Django into three layers:

- The interface layers, initially just WSGI and WebSockets at launch. These are responsible for turning the client connections into channel messages and vice-versa.

- The channel layer, a pluggable backend which transports messages over a network - initially two backends, one database-backed and one redis-backed.

- The worker layer, which are processes that loop and run any pending consumers when messages are available for them.

The worker is pretty simple - it's all synchronous code, just finding a pending message, picking the right consumer to run it, and running the function until it returns (remember, consumers can't block on channels, only send to them - they can only ever receive from one, the one they're subscribed to, precisely to allow this worker model and prevent deadlocks).

The channel layer is pluggable, and also not terribly complicated; at its core, it just has a "send" and a "receive_many" method. You can see more about this in the prototype code I've written - see the next section.

The interface layers are the more difficult ones to explain. They're responsible for interfacing the channel-layer with the outside world, via a variety of methods - initially, the two I propose are:

- A WSGI interface layer, that translates requests and responses

- A WebSocket interface layer, that translates connects, closes, sends and receives

The WSGI interface can just run as a normal WSGI app (it doesn't need any async code to write to a channel and then block on the response channel until a message arrives), but the WebSocket interface has to be more custom - it's the bit of code that lets us write our logic in clean, separate consumer functions by handling all of that connection juggling and keeping track of potentially thousands of clients.

I'm proposing that the first versions of the WebSocket layer are written in Twisted (for Python 2) and asyncio (for Python 3), largely because that's what Autobahn|Python supports, but there's nothing to stop someone writing an interface server that uses any async tech they like (even potentially another language, though you'd have to then also write channel layer bindings).

The interface layers are the glue that lets us ignore asynchrony and connection volumes in the rest of our Django code - they're the things responsible for terminating and handling protocols and interfacing them with a more standard set of channel interactions (though it would always be possible to write your own with its own channel message style if you wanted).

An end-user would only ever run premade ones; they're the code that solves the nasty part of the common problem, and all the issues about tuning and tweaking them fall to Django - and I think that's the job of a framework, to handle those complicated parts for you.

Why Workers?

Some people will wonder why this is just a simple worker model - there's nothing particularly revolutionary here, and it's nowhere near rewriting Django to be "asynchronous" internally.

Basically, I don't think we need that. Writing asynchronous code correctly is difficult for even experienced programmers, and what would it accomplish? Sure, we'd be able to eke out more performance from individual workers if we were sending lots of long database queries or API requests to other sites, but Django has, for better or worse, never really been about great low-level performance.

I do think it will perform slightly better than currently - the channel layer, providing it can scale well enough, will "smooth out" the peaks in requests across the workers. Scaling the channel layer is perhaps the biggest potential issue for large sites, but there's some potential solutions there (especially as only the channels listened to by interface servers need to be global and not sharded off into chunks of workers)

What I want is the ability for anyone from beginner programmers and up to be able to write code that deals with WebSockets or long-poll requests or other non-traditional interaction methods, without having to get into the issues of writing async code (blocking libraries, deadlocks, more complex code, etc.).

The key thing is that this proposal isn't that big a change to Django both in terms of code and how developers interact with it. The new abstraction is just an extension of the existing view abstraction and almost as easy to use; I feel it's a reasonably natural jump for both existing developers and new ones working through tutorials, and it provides the key features Django is missing as well as adding other ways to do things that currently exist, like some tasks you might send via Celery.

Django will still work as it does today; everything will come configured to run things through the URL resolver by default, and things like runserver and running as a normal WSGI app will still work fine (internally, an in-memory channel layer will run to service things - see the proper proposal for details). The difference will be that now, when you want to go that step further and have finer control over HTTP response delays or WebSockets, you can now just drop down and do them directly in Django rather than having to go away and solve this whole new problem.

It's also worth noting that while some kind of "in-process" async like greenlets, Twisted or asyncio might let Django users solve some of these problems, like writing to and from WebSockets, they're still process local and don't enable things like chat message broadcast between different machines in a cluster. The channel layer forces this cross-network behaviour on you from the start and I think that's very healthy in application design; as an end-developer you know that you're programming in a style that will easily scale horizontally.

Show Me The Code

I think no proposal is anywhere near complete until there's some code backing it up, and so I've written and deployed a first version of this code, codenamed channels.

You can see it on GitHub: https://github.com/andrewgodwin/django-channels

While this feature would be rolled into Django itself in my proposal, developing it as a third-party app initially allows much more rapid prototyping and the ability to test it with existing sites without requiring users to run an unreleased version or branch of Django.

In fact, it's running on this very website, and I've made a simple WebSocket chat server that's running at http://aeracode.org/chat/. The code behind it is pretty simple; here's the consumers.py file:

import redis

from channels import Channel

redis_conn = redis.Redis("localhost", 6379)

@Channel.consumer("django.websocket.connect")

def ws_connect(path, send_channel, **kwargs):

redis_conn.sadd("chatroom", send_channel)

@Channel.consumer("django.websocket.receive")

def ws_receive(channel, send_channel, content, binary, **kwargs):

# Ignore binary messages

if binary:

return

# Re-dispatch message

for channel in redis_conn.smembers("chatroom"):

Channel(channel).send(content=content, binary=False)

@Channel.consumer("django.websocket.disconnect")

def ws_disconnect(channel, send_channel, **kwargs):

redis_conn.srem("chatroom", send_channel)

# NOTE: this does not clean up server crash disconnects,

# you'd want expiring keys as well real life.Obviously, this is a simple example, but it shows how you can have Django respond to WebSockets and both push and receive data. Plenty more patterns are possible; you could push out chat messages in a post_save signal hook, you could dispatch thumbnailing tasks when image uploads complete, and so on.

There's not enough space here for all the examples and options, but hopefully it's given you some idea what I'm going for. I'd also encourage you to, if you're interested, download and try the example code; it's nowhere near consumer ready yet, and I aim to get it much further and get better documentation soon, but the README should give you some idea.

Your feedback on the proposal and my alpha code is more than welcome; I'd love to know what you think, what you don't like, and what issues you're worried about. You can chime in on the django-developers thread, or you can email me personally at andrew@aeracode.org.